A Brief History of Cymatics

"The geometry of the shapes is solidified music" - Pythagoras

From ancient Greek: κῦμα, meaning "wave" is what inspired scientist Hans Jenny to use the term Cymatics, to describe a subset of modal vibrational phenomena - the study of visible sound and vibration in the 1960s. Jenny (1904-1972) was a physician and natural scientist. In 'Cymatics: The Study of Wave Phenomena' he concluded about what he had observed, "This is not an unregulated chaos; it is a dynamic but ordered pattern."

And so, Cymatics refers to the study of the periodical effects that sound and vibrations exercise on matter. Cymatics can be described as a field of research studying the observations and the measurements of the vibrational sound frequencies interacting with all kinds of matter.

The first person to leave a written record of this work was arguably Leonardo da Vinci. In the late 1400’s, after observing how the dust on his work table stirred to create shapes when he vibrated the table, he wrote, “I say that when a table is struck in different places the dust that is upon it is reduced to various shapes of mounds and tiny hillocks.” Da Vinci’s close observation of dust under the influence of vibration was, quite literally, sound made visible. Rather like sprinkling powder on a fingerprint to render it visible, a light sprinkling of particulate matter on any vibrating surface will reveal hidden sound patterns.

It was the 1630s when Galileo Galilei reported an experiment where brass dust shapes up into equidistant and parallel lines once subjected to vibrations.

In 1680, Robert Hooke, Oxford University English scientist, described an experiment where he used a violin bow to exercise vibrations onto a glass plate with flour on top and described the “nodal” patterns. What he described was further explored and documented by Ernst Chladni, a German musician and scientist who used a high-resonance copper plate, covered with lycopodyum dust, subjected to vibrations through the use of a violin bow. Different inclinations of the bow would produce different vibrations and corresponding shapes, which we call today ‘Chladni Figures’.

In the late 18th-century he produced Entdeckungen über die Theorie des Klanges (Discoveries in the Theory of Sound), in which he detailed his experiments. He is sometimes labelled the "father of acoustics" for providing a significant contribution to the understanding of acoustic phenomena and how musical instruments functioned. Such patterns are now commonly termed "Chladni figures".

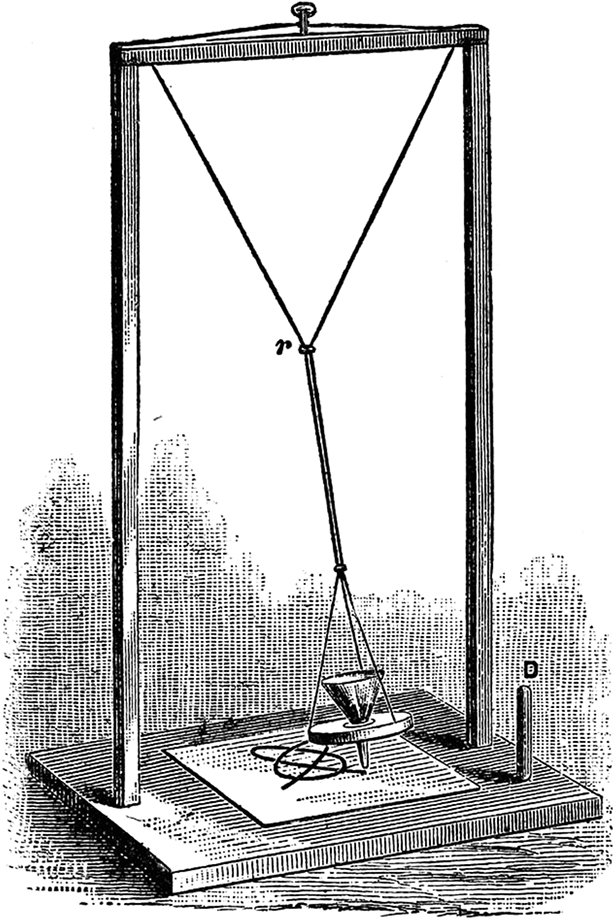

Another example of how sound generates geometric patterns, are the results of H. Irwine Whitty, who studied the connection between music and geometry with the aid of the harmonograph, a mechanical machine that uses pendulums to create geometric figures and drawings. He concludes that “the facts that musical notes are due to regular air-pulses, and that the pitch of the note depends on the frequency with which these pulses succeed each other, are too well known to require any extended notice”, referring to the already established works of Chladni.

Plate VIII, Harmonograph, H. Irwine Whitty, 1893

The Harmonograph is a mechanical apparatus that employs pendulums to create a geometric image. The drawings created typically are Lissajous curves or related drawings of greater complexity. The devices, which began to appear more frequently in the mid-19th century, cannot be attributed to a single person obviously, but Hugh Blackburn, a professor of mathematics at the University of Glasgow, is commonly named the official inventor.

Michael Faraday (1791-1867), english chemist and physician, writes into his diaries about the many experiments he conducted to report the effects of electromagnetic vibrations on water, oils and various types of powders, defined as Crispations. Faraday was fascinated by these phenomena and always very good at demonstrating to his audiences at the Royal Institution.

He wrote about putting a candle exactly below a glass plate and holding a screen of tracing paper an inch above it, the image of the vibrational effects on different types of matter was striking. Each heap of powder or pour of liquid gave a different effect as it appeared and disappeared. At the corners a fainter image appeared, and then as the screen was nearer or farther, lines of light in 2 or even 4 directions appeared consistently. Faraday did not identify any potential applications for crispations and as far as is known never reopened his investigations in this field.

Lord Rayleigh, an English physicist and second Cavendish Professor of Physics at Cambridge University, earned the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1904, along with William Ramsay, for the discovery of the element argon. He also discovered surface waves in seismology, now known as Rayleigh waves. His major treatise, 'Theory of Sound,' in two volumes, includes a chapter on the 'Vibrations of Plates' as well, and is still considered an important work. In it he explored “nodal” phenomena in depth.

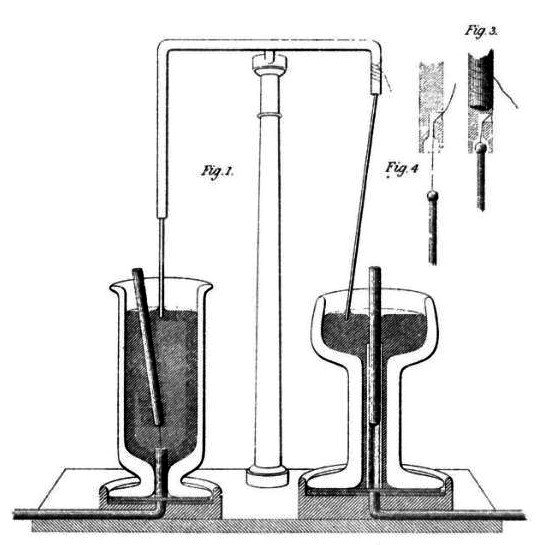

At the dawn of recorded sound history, it was as much a visual translation as an auditory one. The phenomenon of recording music relied upon the act — via the medium of a vibrating surface — of converting sound waves into physical motion, and a subsequent act of inscription on a surface that could be repeated. The earliest practical example of such a recording apparatus was Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville's Phonautograph. Patented in 1857, it consisted of a vibrating diaphragm, lever, and a hog's bristle brush which scratched sound into soot-coated paper or glass. Scott de Martinville conceived the marks produced as a form of "auto-stenography", where the inflections and intonations of an individual sound might be read by anyone with the required patience to learn this new form of "script". This “visibility of sound” fuelled much debate between artists, musicians, scientists, and even lawyers about what precisely these scratches and squiggles constituted. Were they a kind of writing, an expository method of display and measurement, or a mutable and plastic material — a site of aesthetic transformation and potential production? These aesthetic concerns grew to become well established in the more esoteric and expressionistic visual and musical practices of the late nineteenth century.

Leon Scott de Martinville's Phonautograph, 1857

Alexander Graham Bell as well felt compelled to commingle the auditory and the visual when he invented the Photophone. He exclaimed to his father:

“I have heard articulate speech produced by sunlight! I have heard a ray of the sun laugh and cough and sing!... I have been able to hear a shadow, and I have even perceived by ear the passage of the cloud across the sun's disk!”

Illustration of the Photophone's transmitter, from El mundo físico (1882) by Amédée Guillemin

This ingenious device consisted of a mouthpiece attached to a chamber capped with a thin mirror. When spoken into, the mirror would vibrate, thereby modulating a beam of sunlight — effectively encoding it with the sound. This vibrating light beam was then picked up and turned back into sound by a mirrored parabolic receiver some distance away. As Steven Connor has noted, the communications landscape of the late nineteenth century was characterised by "a kind of conversion mania, as inventors and engineers sought more and more ways in which different kinds of energy and sensory form could be translated into each other.”

The popular singer and philanthropist Margaret Watts Hughes entered this field with a device similar in most respects to Bell's Photophone. Her "Eidophone", which she conceived of and produced in order to measure the power of her own voice, consisted of a mouthpiece leading to a receiving chamber, over which was stretched a rubber membrane. Her experiments with this device involved sprinkling a variety of powders onto its surface, then singing into it to see how far these powders would leap. As she observed:

“I had been working on this path until May, 1885, when on one occasion as I sang I noticed that the seeds which I had placed on the India rubber membrane, on becoming quiescent, instead of scattering promiscuously in all directions and falling over the edge of the receiver onto the table, as was customary when a rather loud note was sung, resolved themselves into a perfect geometrical figure.”

Illustrations of these phenomena, which she termed Voice Figures, can be found in an article in the Century from 1891. Arranged in order of increasing complexity, the figures display a clear hierarchy of forms, from the simple "primitive" and geometrical, to more complex figures that look more like floral shapes.

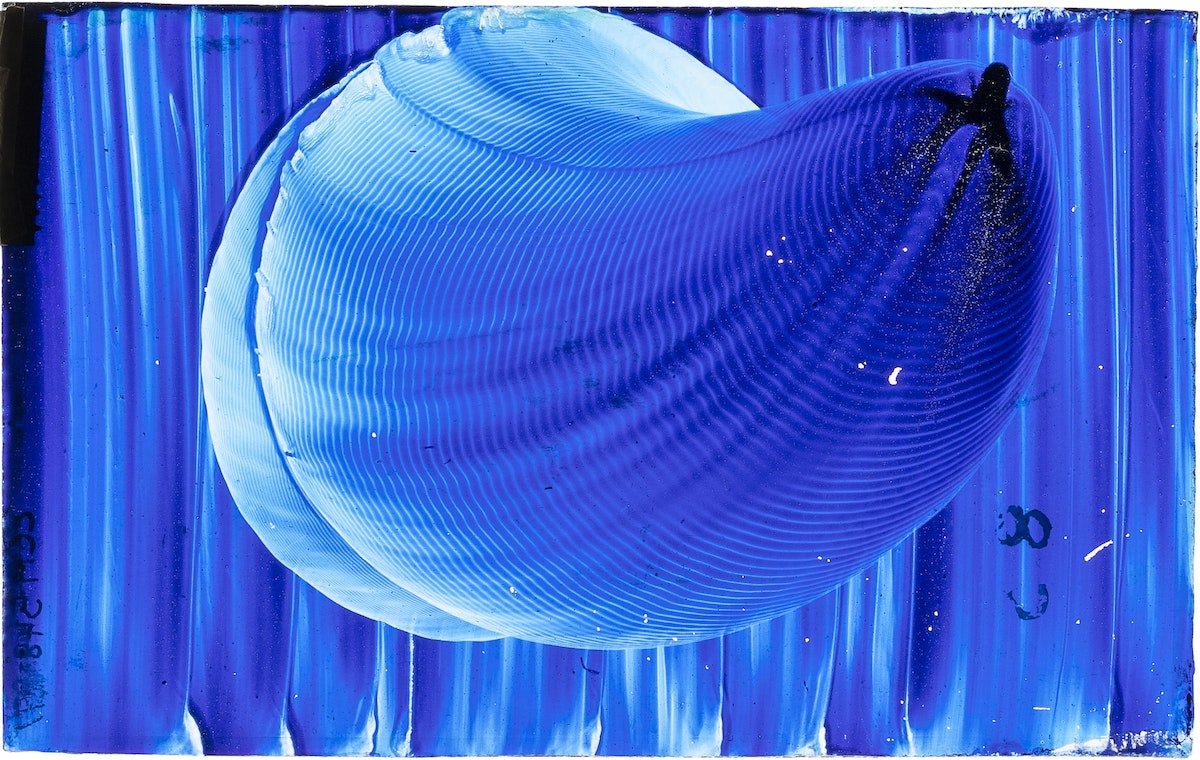

We know that she went on to experiment with placing various consistencies of pastes and liquids on the instrument as a way of introducing binding mediums to "fix" the figures she made, resulting in a series of figures that both resembled and were named after flowers. These images were produced by placing the Eidophone's diaphragm face up: the figure would then be sung into existence, and the glass plate then placed on top to capture it.

The following is a group of works she called “Impression Figures”, which I think are by far the most visually and symbolically rich of the images she produced. These were made by coating a glass plate and the diaphragm of a Eidophone with pigment, then passing it over the plate's surface while singing a note into its mouthpiece.

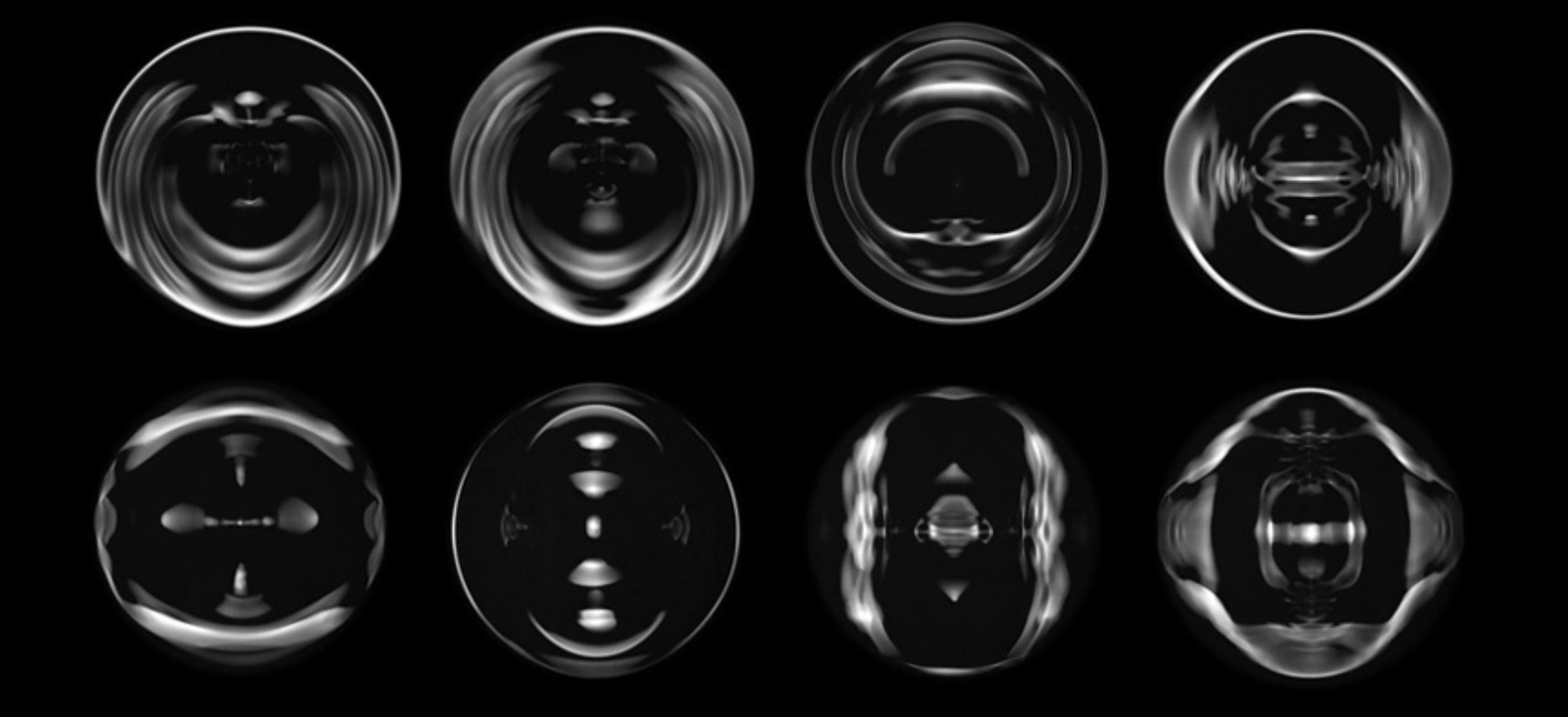

Mary Desiree Waller (daughter of a famous English physiologist, August D. Waller) became fascinated by Chladni’s work and recreated all the forms he discovered, taking his work to a higher level. Her book ‘Chladni Figures, a Study in Symmetry was published posthumously in 1961 and includes details of her novel method of exciting plates employing solid carbon dioxide chips. She approached the subject of Chladni Figures with scientific rigor and her work represents a rich resource for students of this branch of acoustics, including some of the mathematical equations that describe the phenomena.

Mary Desiree Waller, Chladni Figures, a Study in Symmetry, 1961

Moving from these important inventors, a wide range of artists and practitioners have explored the natural phenomenon of sound resonance. Most famous for his work on how water crystals change under the vibrational effect of various words Dr Masaru Emoto, also studied how different types of music affect water molecules. The Emoto music studies demonstrate how certain types of sound, like classical music played in the 432 htz range, generate beautiful crystalline patterns, while jarring music played in the 440 htz range, generate ugly and distorted crystalline formations. In the images below you see the crystalline formation resulting from water being exposed to Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 and then in contrast what the water crystal image looks like after being exposed to AC/DC’s anthem Highway to Hell.

The inspiration for the exploration of Cymatics, as a field is steeped in “anthroposophy,” a philosophy founded by Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), which states that human beings can intellectually access and uncover elements of an existing spiritual plane, and the person who made arguably the largest contribution in the twentieth century was Hans Jenny (1904–1972). Jenny was a Swiss medical doctor and scientist who published his first volume, Kymatic—a title derived from the Greek word kuma (wave), a description of the periodic effects that sound and vibration have on matter in 1967, and his second in 1972. His two volumes are a visual inventory, which he observed and described in great detail while leaving scientific and mathematical explanations to scientists who would come after him.

Hans Jenny studied visual sound intensively. As a physician, fine artist, pianist, philosopher, historian, and empirical researcher, Jenny conducted a wide range of experiments documenting the effects of sound and energy on various media.

He also documented his experiments in 16mm films entitled Cymatic SoundScapes, Bringing Matter to Life with Sound.

Most ancient cultures used the seemingly magical power of sound to heal. Sound healing had almost disappeared in the west until the 1930s when acoustic researchers discovered ultrasound and its medical properties. With this discovery, research burgeoned and today the ancient art of sound healing is rapidly developing into a new science. Cymatics are playing a significant role in these new applications.

The Aboriginal people of Australia are the first known culture to heal with sound. Their ‘yidaki’ (modern name, didgeridoo) has been used as a healing tool for at least 40,000 years. The Aborigines healed broken bones, muscle tears and illnesses of every kind using their enigmatic musical instrument. Interestingly, the sounds emitted by the yidaki are in alignment with modern sound healing technology. It is becoming apparent that the wisdom of the ancients was based on ‘sound’ principles.

The Egyptian culture extends back to 4000 BC and they have a long tradition of vowel sound chant. A Greek traveler, Demetrius, circa 200 B.C., wrote that the Egyptians used vowel sounds in their rituals:

‘In Egypt, when priests sing hymns to the Gods they sing the seven vowels in due succession and the sound has such euphony that men listen to it instead of the flute and the lyre.’

The Corpus Hermeticum also contains a reference to the Egyptian’s use of sound as distinct from words. This book was probably related in the 1st century AD but it is believed to be much older, possible as early as 1400 BC. The Egyptians believed that vowel sounds were sacred, so much so that their written hieroglyphic language contains no vowels. We can, therefore, safely assume that vowel sound chant carried a powerful significance for their priests.

Egyptian priestesses used sistra, a type of musical rattle instrument with metal discs that creates not only a pleasant jangling sound but, as we now know, also generates copious amounts of ultrasound. Ultrasound is an effective healing modality and is used today in hospitals and clinics so it is entirely possible that ceremonies in which many sistra were used were not merely employed to enhance the musical soundscape but were intended to enhance the healing effect.

In the wall scene below, from a building erected by Queen Hatshepsut, three priestesses play sistra, accompanying a harpist, another instrument known to have healing qualities.

The Greek, Pythagoras (circa 500 BC) was, in a very real sense, the father of music therapy. The Pythagoras Mystery School, based on the island of Crotona, taught the use of flute and lyre as the primary healing instruments and although none of Pythagoras’ writings have come down to us we know of his philosophy and techniques from many contemporary writers. With his monochord—a single-stringed musical instrument that uses a fixed weight to provide tension—Pythagoras was able to unravel the mysteries of musical intervals.

Lamblichus noted that:

‘Pythagoras considered that music contributed greatly to health, if used in the right way…He called his method ‘musical medicine’…To the accompaniment of Pythagoras’ his followers would sing in unison certain chants…At other times his disciples employed music as medicine, with certain melodies composed to cure the passions of the psyche…anger and aggression.’

Dr Peter Guy Manners, was an English Osteopath, and pioneer in using sound to heal. He studied Dr Jenny's Cymatics and created Cymatics therapy. Dr Manners correlated different harmonic frequencies that are the healthy resonant frequencies of various parts of the body. He researched the use of Cymatics for medical diagnosis and treatment, including the healing effects of certain sound vibrations and harmonics on the structure and chemistry of the human body as well as the importance of sound and light in our natural environment. Cymatics therapy uses a toning device to transmit into diseased areas of the body the signature vibrations of healthy organs and tissues. Dr Manners designed a machine that would deliver frequencies directly to the body using an applicator. There are over 700 frequencies that can be transmitted through this tool to help normalize imbalances and synchronize the cells' frequencies back to their natural, healthy state of vibrational resonance. Sound is capable of rearranging the structure of molecules, and therefore has unlimited potential as a tool for healing. A form of sound therapy that is not applied through hearing, but by instruments that send audible sound waves directly into the body through the skin.

John Stuart Reid, english acoustic engineer, and inventor of the Cymascope, has continued this work with a device able to display frequencies in water in the form of geometrical shapes which he refers to as Cymaglyphs, a term he personally coined. Reid’s acoustics research in the pyramids has provided strong evidence that the Egyptians designed their chapels and burial chambers to be reverberant in order to enhance sonic-based ceremonies. Reid underwent a significant healing of his lower back during his experiments in the King’s Chamber that he attributes to the resonant properties of the sarcophagus. He conjectures that the acoustic resonance was deliberately contrived by the Egyptian architects and thinks it very likely that they were aware of the healing properties of sound long before the Greeks.

Returning to the use of vowel sound chant—the production of vocal sounds rather than words—many eastern cultures developed variations of chant for healing and for spiritual ascension. Studies have shown that vowel sound chants can bring about many positive physiological changes in the body, and create an altered state of consciousness in which the chanter becomes serene and healthy.

Mandara Cromdell is the Founder and Board President of ISTA (The International Sound Therapy Association), and producer of Cyma Technologies AMI 750, a frequency generator created for multiple healing modalities. She has also done extensive study on the relationship between vibrational frequencies and spirituality in India, England and the US, and she frames her explorations around the “Art of Sacred Sound”. He book “Soundflower” is the story of a woman whose divine quest began as a child with a mystical experience in the Gothic architecture of a church. Signs and symbols experienced in her youth continued to appear throughout her life, but one of the most profound spiritual messages came to her from science in the form Cymatics - sound made visible.

At a recent conference Mandara discussed the origin of the Shri Lanka Yantra and it’s origin in terms of the syllable arrangement in Sanskrit. Each mantra is in fact a combination of syllables whose resonant frequency effect specific reflex points in the human mouth. They are also correspondent to the human chakra system and intended to be chanted in spaces of precise resonant design.

The Sri Yantra is a good example of this intention, and is produced cymatically when “Om,” the Hindu primordial sound of creation, is intoned into a tonoscope. The shape of the Sri Yantra, a self-similar, fractal interlaced tetrahedra within concentric circles is the visual representation of the Om chant, intended to match the vibration behind the cosmos, that is the “sound” of the aetheric medium or “fabric” of space. It seems that Hindus have known for thousands of years that sound possessed geometry, or sound into form is a fundamental truth of reality. The Om chant itself is one for expanding consciousness by developing resonance with the cosmos, and I have no doubt that participants experienced the sound in 3-4 and 5 dimensions during practice. The Sri Lankra is simply a 2D tool that represents dimensions, frequencies and possibilities.

Contemporary German photographer, philosopher and Cymatic researcher, Alexander Lauterwasser has brought the work of Hans Jenny into the 21st Century using finely crafted crystal oscillators to resonate steel plates covered with fine sand and also to vibrate small samples of water in Petri dishes. His first book, “Wasser Klang Bilder” (Water Sound Images) features imagery of light reflecting off of the surface of water set into motion by sound sources ranging from pure sine waves, to music by Ludwig van Beethoven, Karlheinz Stockhausen, electroacoustic group Kymatik (who often record in surround sound ambisonics), and overtone singing. In 2006, MACROmedia Publishing published the English version of the Lauterwasser book titled Water Sound Images.

John Telfer uses various types of matter to visualize sound vibrations...including bubbles! If a bubble is vibrated with a low frequency sine wave it adopts steady states of vibration. For Telfer an artist and musician, the structuring of tonal space based on harmonics is significant. After discovering Hans Jenny’s Cymatik, he has worked to bring his musical and visual interests together in images that illustrate the force of sound, such as these single bubbles exposed to various sound frequencies.

Before first bringing his performance to television in the early 80s, Tom Noddy spent over a decade developing a new kind of performance piece. Sitting alone with dime store bubble solution, a childlike sense of wonder and an adult sense of humor he brought a new thing into being: Bubble Magic. Bubble magic as well takes it’s cues from geometry and particle theory. Each bubble sculpture he creates illustrates the intelligence and design within nature made visible with a thin membrane and air.

Shannon Novak, a New Zealand-born fine artist, commissioned the imaging of 12 piano notes as inspiration for a series of 12 musical canvases using the Cymascope Technology developed by John Stuart Reid.

Shannon was delighted with the results and commented:

“I have always been fascinated with the translation of that which is invisible, into something visible that individuals can relate to, in particular, the representation of sound through colour and geometric form. I saw the use of cymatic technology as one method of such representation and a unique and compelling way of educating individuals about the link between sound, colour, and geometric form“.

Cymatechnologies used the video footage of the same 12 notes within the CymaScope app for Apple and Android platforms. The app is a very fun and easy way to visualize everyday sounds as well as music, and you can download it HERE

Another creator who has used a wide range of materials to illustrate vibrational frequencies is David Schiermeyer. Schiermeyer has experimented with cymatics on water) in deeper and more dimensional ways with surface area rotation and dimensional structures of undertones and frequencies themselves. He works with plasma and static resonance to develop technologies like the life viewer, which was the first visualizing equipment I tried myself.

Life viewers are cymatic kits for creating and studying the structures of a frequencies’ behavior, music, or soundscape in water or your choice of fluid mediums. you can get your own HERE

“Frequencies are only patterns to their own surroundings, just like us. As beings we can only experience what our surroundings offer. What matters is how we use that experience. We tune into different channels just like a mixing board, our minds separating current and frequencies. We can auto-tune our mind by adjusting our tone, our thoughts, our actions. We are the living experience of cymatics. We are the experience of living information. We are the experience of our surroundings, and our surroundings are experiencing through ourselves. Once we grasp this as a species there will be a true evolution of being.”

—David Schiermeyer

Be sure to check out David’s YouTube channel and TikTok for videos like this.

Now of course I have only touched on a brief history here, but there will be more to come as I continue my own research and experiments. I will leave you with a beautiful example of cymatics applied in various ways through the music of Nigel Stanford titled CYMATICS: Science Vs. Music.

Enjoy!